Escape from Serfdom

Master the Dark Arts of Corporate Warfare to Achieve Financial Independence

“They say hard work never killed anybody; I say, why take the chance?”

Ronald Reagan

"You fight and die to give wealth and luxury to others; you are called the masters of the world, yet there is not a foot of ground that you can call your own."

- Tiberius Gracchus

Introduction

Sometimes a particular event occurs and forces you to take serious stock of where you are, how you got there, and demands some hard decisions about your future intentions. One such event happened to me a few years ago, and it’s the reason I wrote this book. More to the point, it’s the reason I had to write this book.

I will share this story with you in a moment. First, some context about your author.

Who I am is not important. There are many people similar to me out there in the world today. When you read disparaging commentary in the media about the globalists, the centurions of international capitalism, attending top universities and then gallivanting around the planet on business class flights and staying in luxury hotels, dining at the finest establishments as the world burns – that’s me. I was not born into generational wealth, but nevertheless did enjoy a relatively privileged upbringing, all things considered, of which I subsequently took full advantage in my professional career. I am wealthy after a fashion, but not remarkably so by today’s standards. I climbed to the higher (but not the highest) echelons of corporate power; in the end I was too much of an iconoclast to be handed the keys to the car, as it turns out.

This was probably for the best, honestly.

I’m not saying any of this out of self-aggrandizement, but rather to give you a bit of perspective on where I’m coming from. I have spent thirty years working at all levels of the corporate threshing machine in dozens of countries, as a junior employee, as an executive and a consultant, in strategy, technology, regulation, marketing and finance. I have started several of my own businesses; some have succeeded, some have failed. Again, none of this is remarkable or extraordinary. But I have paid careful attention to everything I have seen and heard along the way. This journey has not been without adventure, and has taught me some valuable lessons. Those lessons are what I want to share with you today.

I’m not asking you to listen to me because I’m fabulously wealthy, or was CEO of a multibillion-dollar corporation, or am some kind of rarefied, planetary level genius. I’m not. But I am prepared to be honest with you, which most people aren’t. What I can offer is an unvarnished view into what happens on the factory floor and explain to you how the sausage gets made, as they say. More importantly, I can give you a guide on how to make your escape from the factory before getting turned into sausage yourself.

This will have to suffice as an introduction.

A couple years after having left an executive Vice President role at a company in whose mission I truly believed and was very proud to work for, one of my old staff approached me for advice and help. I expected she wanted a reference for a job or some such, which unfortunately turned out to be far from the case. She arrived at my house for coffee one sunny spring afternoon with a smile on her face, but a peculiarly clouded and troubled expression. After some pleasantries, she opened her phone and handed it to me. What I saw was shocking, and well, gross.

There were hundreds of WhatsApp messages from the recently appointed CEO of our company, blatantly sexual in nature. There were numerous photos of him in flagrante. The details of the messages are not important, but this was a case of sexual harassment of the most sordid and revolting kind.

Now, this woman was happily married with two children and had done nothing to encourage such an approach. She was deeply shaken and told me she was determined to leave the company. The CEO was using his vast power to hinder her career and constantly toyed with her professional ambitions (she was a very ambitious and driven lady), offering an obvious quid pro quo of advancement in exchange for a sexual liaison.

Well, what do you want, I asked her. I pointed out that in some respects, while the situation was unspeakably awful, this witless creep had handed her a winning lottery ticket. He was the local representative of a major multinational, publicly traded corporation that made much of its mission regarding equality, diversity and inclusion. They would never tolerate such behavior and would probably be willing to pay virtually any sum to prevent it from ever coming to light. The messages in her phone were pure gold, I told her. Should she be so inclined, I offered to help find her an appropriate lawyer in the jurisdiction where the company was traded. She would surely be in line for a seven-figure settlement in a matter of weeks.

She shook her head. She and her husband were already quite wealthy. I don’t want to be known as the woman who tried to get rich off of this, she said, quietly, I just want to make sure he won’t do it to anyone else, especially anyone not fortunate enough to be in my financial position, with the ability to say no.

I agreed that this was an absolutely laudable and selfless perspective. In that case, I said, let’s write a letter to the global director of human resources and explain why you are resigning your position. You can trust them to do the right thing, I said. They will be as horrified as I am, and I’m sure they’ll take care of you.

This was, without a doubt, the single worst piece of advice I have given anyone in thirty years of professional life.

The letter was sent. An investigation was launched. The CEO admitted everything, blaming it on the scorpion woman who had employed every conceivable form of feminine sorcery to entrap him. Within a week he had been relieved of his duties and it was announced to the press that he had decided to spend more time with his family. He is rumored to have received an eye-watering payout from the company in exchange for his silence. In any event he was able to fund a start-up a few weeks later, which he populated with numerous people poached from the same company. As far as I can tell, he remains happy, wealthy and successful in spite of (or because of?) his vile behavior.

The victim in this case did not fare quite as well. I have since learned that this is not an uncommon outcome. I am ashamed to admit that I did not know that sooner. Our former employer did not ask her to rescind her resignation as I expected they would; in fact, they did not contact her at all. They left her on the side of the road like a bag of trash. The ‘crazy scorpion woman’ narrative began to cascade through the industry. She could not find work, as she was now labeled a madwoman and troublemaker. She spiraled into depression, eventually being institutionalized after an attempt to take her own life.

I called a lawyer friend (coincidentally another old colleague from the same company) and related the situation, with the intention of getting advice about initiating litigation. I also wondered aloud, how could this of all companies behave so piggishly to a woman who was so clearly in the right, who had devoted so many years of service to them, and on a topic of such vital importance to the firm’s essence and identity? The lawyer, kindly and not in so many words, said ‘Well, to be honest this doesn’t surprise me. Any competent lawyer would recommend them to act this way and never contact her again. I would have given them the exact same advice. Now we both know it’s morally wrong, but I would have a duty of care to them as my client to give them the legally correct advice. And if you were still an executive there, you would also have a duty of care to act on that advice. So please don’t blame our old colleagues personally. They’re only doing what they are bound to do, given their positions.”

Her words struck me as oddly, almost offensively, dismissive at first. But after we finished the call, I considered them more carefully. The more I turned them over in my mind, the more evident it became to me that she was completely correct, and the more horrified I became. Had I still been a member of the executive at that moment, I would have been confronted with an excruciating choice: go along with unambiguous legal advice and honor my obligations of due care toward my shareholders, or resign a prestigious, comfortable, enormously influential and well-compensated role. It is easy to say that I would choose the latter out of principle; I am not so naïve or cocksure to say I know for a fact what I would have done. Galadriel did not know what she herself would do until the moment she saw the One Ring freely offered in Frodo’s outstretched palm, after all, and did not pretend otherwise.

My old employee is since recovered and doing much better, though she has never worked since that day and probably never will. She is part of the ‘ladies who lunch’ crowd, reads a lot, and seems reconciled to her new lifestyle. We are in touch with each other regularly.

These events started me on a long journey of careful consideration about the nature of the modern corporation, how it treats employees, and the fraying social contract that exists between the two. The conclusions I have drawn surprise even me. The fact that they surprised me compelled me to write this book; if they startle even me with their fierce urgency after so many years of professional life, I expect they must be of some interest to those just beginning their own journeys.

This book is not for everyone. It is for young professionals in the beginning or mid-point of their corporate careers; perhaps just beginning to assess goals and aspirations, perhaps confronted by some awful choice that has sounded a clarion call of urgency in their mind. It is not for budding entrepreneurs, captivated by the dream of starting and running their own businesses. While they may find this book of some passing interest, these lessons are not intended for them. It is not for senior executives: they already know everything written here, and they’ll just get angry that someone has broken the code of omerta and let the cat out of the bag. Nor is this particularly intended for those seeking only to collect a paycheck and somehow muddle through life. I address this book to those with ambition coursing through their veins, and a restless determination to achieve something of note during their brief stay on a fragile planet, within the confines of the corporate world.

I don’t want to say that I have myself followed all the advice in this book. I wish I had; I would be a wealthier man today. Some of it stems from my successes, but much of it derives from mistakes and failures. A great deal comes from careful observation of others who have succeeded or failed in various circumstances. I am at heart a student of history, of economics and the human psyche, but I cheerfully admit that my actions are not always informed by my hard-won wisdom. Think of me as the notional short, overweight, melanin-deficient basketball coach who has the vertical leap of a snapping turtle but is nevertheless able to stimulate and encourage superior performance in those with the prerequisite native talent. I am a consigliere to the mighty, whispering wisdom from impenetrable shadows in the halls of power, avoiding the spotlight at all costs.

Today, I am your guide on your escape from serfdom, if you will have me.

1. Why work?

“If you don’t know where you’re going, you might end up somewhere else.”

- Yogi Berra

Why do we work?

The question seems banal and absurd on its face. We work to live, to survive. Work allows us to get paid, and purchase food, shelter and clothing. If you’re lucky, save a bit, buy a house, consume, perhaps conspicuously. Start a family, have some kids. Give them the same life you had growing up, maybe a bit better. Retire with your sense of self and dignity intact.

Many people leave it at that, and that’s fine. However, at a certain point in your career, you may begin to reconsider the answer to that question; or rather, to refine it further. Is that really all there is? Should I not be seeking fulfillment, as well as simple subsistence level compensation? Do I not have the right to be stimulated intellectually, to grow my skills and expand my horizons? Do I seek authority, renown, or power? Why should I not be obscenely wealthy? Can I not find a place in the economy where I do not merely fulfill the requirements of an ever more ravenous consumerism, but make the world a bit better, a bit safer, a bit more just and humane?

Many people begin to consider these questions fitfully and opportunistically, generally in response to a particular situation or unexpected crisis. They rarely give it structured and serious thought until later in their career, informed by whatever path they happened to stumble down until that point. Paradoxically, at the point in one’s career when such careful consideration would do the most good – at its inception– one is least equipped to arrive at a satisfactory answer. Up until that point most people’s experiences are from low-level jobs, surrounded by the well-intentioned but largely doltish and ignorant associates of one’s youth. They may have some observations from their parents’ lives, or relatives, or stories from their friends, but these stories are full of holes and important gaps, lack context, and are always burnished to show the protagonist in a better light than reality would probably reflect. At this age one is fed with platitudes, molded by the expectations of one’s family and immediate environment, and likely to come to impossibly naïve and frequently ridiculous conclusions about what one wants from the impending decades of indentured servitude to capitalist overlords. Extricating oneself from this invisible web of half-whispered expectations is difficult, psychologically taxing, and consumes the most valuable and irreplaceable of all assets: time.

Warren Buffet once commented, “Time is the only thing I cannot buy.”

My first wife’s father was forced into early retirement and died of cardiac failure a few weeks later. This was of course unexpected, and deeply tragic. The commonly received wisdom was that he had been so involved in his work, his persona so tied up in his career, that he simply lost the will to live. Now, all this may have been pure coincidence. In retrospect, it most likely was. But I remember thinking at his funeral service how incredibly depressing this notion was.

From one point of view, he’d been freed from drudgery at a relatively early age. The family was financially secure, and he had decades of puttering around the house and enjoying his numerous grandchildren to look forward to. What a gift this potentially could have been! But instead of a gift, this man saw it as an unbearable loss, by all accounts at the level of losing a spouse. But why? To what end? The details at this point are immaterial. Suffice it to say his career was successful, but not notably so, in a field of work that was clearly on its last legs in that part of the world – hence the wave of involuntary redundancies and ‘for sale’ signs waving forlornly in the front yards of most of the decrepit houses in his village. Not to mention environmentally destructive in the extreme. While the company was vital to the local economy, it may as well have been a VCR factory for all the perspective it had, or a landmine manufacturer in terms of social good. Yet this kind, decent, intelligent man had found existentially vital meaning in his work1.

I have worked my whole life in the technology sector. This has always seemed to me to be a field with purpose. After all, technology has led to productivity gains that have lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. Mobile phones have fulfilled Nikola Tesla’s century-old prophecy of an interconnected world-brain in everyone’s pocket. My children have the entire massed knowledge of humanity at their fingertips at an age when I was pawing through encyclopedias to write papers for school while barely skirting accusations of plagiarism. Email and Microsoft Excel are surely peers with the steam engine or the cotton gin in terms of precipitating a revolution in labor productivity. Anyone who can remember trying to find a hotel in the Austrian Alps at night during a snowstorm by staring at a paper map will agree that online navigation apps are one of the most useful inventions of our generation. Simply put, for the majority of my career, I felt that what I was doing was unambiguously good. Not only for myself and my bank account, but for all humankind.

Things are rarely so simple, of course. The technology industry over time has morphed into an agglomeration of monopolies and oligopolies. Telecommunications has always been a series of government approved oligopolies in any event, unavoidably perhaps due to economics of networks and the scarcity of spectrum. Formerly purportedly rebellious, customer-centric brands such as Amazon, Google and Apple have turned into some of the most abusive monopolists in history on a par with Standard Oil and its ilk, promises to “not be evil” notwithstanding. The monstrous political, social and moral consequences of the commercial and national security total surveillance regimes have only just begun to emerge. Billions-strong fleets of all-seeing nanodrones will soon be floating around the planet, nothing and no one hidden from their unblinking gaze. We are pushed, harried and nudged into behaviors and opinions by the omnipresent, invisible web of social media in a manner that would have been inconceivable a decade ago and is the envy – and plan – of any would-be dictator. As Shoshana Zuboff succinctly puts it in her fantastic book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, “It is no longer enough to automate information flows about us; the goal now is to automate us.” In the book, she paints a fearsome portrait of what is waiting for us as a species beginning to merge with the fruits of its own technology, which is worth quoting at some length:

“Imagine you have a hammer. That’s machine learning. It helped you climb a grueling mountain to reach the summit. That’s machine learning’s dominance of online data. On the mountaintop you find a vast pile of nails, cheaper than anything previously imaginable. That’s the new smart sensor tech. An unbroken vista of virgin board stretches before you as far as you can see. That’s the whole dumb world. Then you learn that any time you plant a nail in a board with your machine learning hammer, you can extract value from that formerly dumb plank. That’s data monetization. What do you do? You start hammering like crazy and you never stop, unless somebody makes you stop. But there is nobody up here to make us stop. This is why the “internet of everything” is inevitable.”

As a technologist I can confirm this is what is happening. The change is faster, more profound and far more dangerous than people - even the paranoid doomsayers - believe.

I took a walk a couple of years ago during the COVID lockdowns with a relative. He’s an uncomplicated man, who works in building maintenance. Generally credulous, I realized he had fallen into the conspiracy ratholes in vogue at the time. He asked me with very real and palpable concern, “hey, you work in technology, you understand this stuff. Did Bill Gates really put microchips in the vaccine to track us?” I tried to keep a straight face and explained to him the physical impossibility of this (what power source would it use to broadcast information? How would a microscopic antenna communicate with a receiver hundreds of meters or kilometers away? What sensors and processors would there be to catalogue, code, and track the requisite data? Etc.)

Anyway, I told him, if you’re worried about what the vaccines in your blood might be broadcasting about you, you’d better take that telephone out of your pocket and chuck it in the river immediately. Because it’s definitely doing far worse things than you can possibly imagine at this very moment. It knows everything you do, and I mean everything. And that information is packaged up and sold to whomever is willing to pay for it, for whatever purpose and to any end, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

He nodded worriedly and we moved on to other topics. He and his wife are still unvaxxed, and he still carries the same phone in his pocket. I haven’t asked him why.

I was recently contracted to advise a Middle Eastern regulatory authority in the course of enacting some new anti-monopoly and consumer protection rules. During one discussion they were worried if the proposals were not too strict and what the effect might be. I told them, guys, this is a regulated oligopoly and these companies will behave like amphetamine-crazed, feral pigs at the trough if you let them. For every one of me you’ve hired, these companies you’re trying to regulate will have ten people exactly like me combing through these rules looking for any gap, any hole, any inconsistency to litigate or exploit. I spent my whole career going around, over, or wiggling through regulation and believe me, these guys will still find a way to screw consumers no matter how hard you try to stop them.

They seemed nonplussed by this idea. I related to them how once I had brought suit against a rival firm and flew to the European Commission in Brussels to explain why they were such a band of anti-competitive jerks and this particular thing they were doing was going to hurt not merely my company and my shareholders, but all of the poor innocent consumers in Europe. Two years later I was working for the company against which I’d previously brought suit, and was back in Brussels, arguing the same case from the opposite point of view and telling them how it was completely unproblematic and actually very beneficial to consumers everywhere. Now I consult on the topic for other companies in similar situations around the globe. The moral of the story being, there is no right and wrong, no true or false, just people regurgitating what they are paid to by whomever happens to be footing their bills that month.

I have a friend … well, not exactly a friend, he’s in that odd space where you are closer than pure work acquaintances but not friends as such, if you see what I mean. I like him personally quite a bit. He’s a decent fellow, with a subtle, perceptive and inquisitive mind, a committed family man, and very particular and conscientious about the quality of his work. I hope he feels the same about me. When one of us happens to be in each other’s part of the world, we make a point of looking the other up for dinner or drinks.

At any rate, three or four years ago he left our company and joined the board of directors of a tobacco manufacturer. This surprised me. After all, the tobacco business at this point is just above child trafficking in terms of moral reputability, but not by much. I presume if you would ask a hundred university graduates today what industries they would refuse to work for, at least ninety would give tobacco as their first response. Yet here was this good-hearted, intelligent, educated man taking on not merely employment but a role of statutory authority with this company in a developing nation with prevalent tobacco usage. How could he possibly accept such a role, I asked myself. I haven’t actually asked him. I cannot imagine a way to pose the question in an objective and non-judgmental manner, though I would very much like to hear his thoughts on the topic.

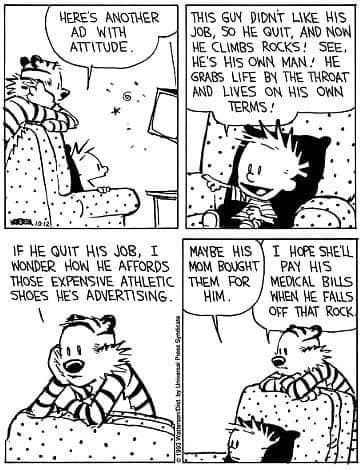

Once, early in my career, a colleague in our fashionable technology company was leaving to go work for Unilever, or maybe P&G. In any event, he was going to go work in marketing for their diaper division. I found this cause for much hilarity. How could anyone possibly leave all this to go sell diapers, of all things?

At the time I worked for this very strange little Dutchman. When I chortled about our colleague to him, he looked at me with incredulity. “Do you have any idea how hard it is to get one of those jobs?” he demanded of me. “They take only the best of the best. I would love to sell diapers.” He explained to me his thoughts in some detail, which I will recount here as best as I am able. Diapers encompass the most fundamental of all needs; that of a mother to keep her baby clean, hygienic and comfortable. It’s the Jungian archetype of all consumer products; the ur-product, if you will. He explained how one well-known diaper brand had confronted a certain commoditization of the sector back in the 80s. After an intensive series of researches and in-home visits with new mothers, they came with a revolutionary approach: “His and hers diapers. Because boys and girls are different. Why shouldn’t their diapers be?” was the slogan, apparently. Genius. Sales and profits skyrocketed.

A couple of years later the wave had passed, the euphoria faded. How to recapture that old magic? The same people in the same marketing department were tasked to revitalize the proposition. After much deliberation and customer dialogue, they came with a new proposition which is, perhaps, the purest distillation of marketing genius. My oddly lumpy, cherubic Dutchman acted out the famous advertisement in his office while his staff gawked and marveled at his antics. Imagine a new mother, at her wits end, standing by two cradles. She’s just had fraternal twins. She looks at two boxes of his and hers diapers, one empty. “If only there were one for both,” she muses hopelessly. Thank goodness our favorite CPG brand has come to the rescue with their “New, universal diapers. Finally, one that fits all!” For the modern working mother who cares about her child but doesn’t have time to waste in the diaper aisle of the supermarket!

My boss hooted with laughter at the pure, unadulterated nihilism of it all. “Don’t you see? They created a need out of nothing, then used that to create a completely new need! Genius! Pure genius!” And all of it riding on the jittery insecurity of the millions of new mothers minted every month, wanting desperately to do the right thing by their purple, squalling little crotch goblins.

This series of anecdotes may seem a bit random and unconnected. However, there is a common thread between them. The point that I have taken from them, and that I want you to take from them, is that what one does for work is completely meaningless. There are no ‘good’ and ‘bad’ companies out there, some providing value for people at large and others simply extracting an indefensible shareholder surplus from ignorant consumers. There is nothing inherently better about writing code for Google than selling chewing gum; the only difference in the size of the paycheck. We are all oxen tethered to the wagon of corporate exploitation. The companies that claim to have broken the mold and aim to do something different inevitably are exposed as the worst offenders and the most egregious charlatans. Elizabeth Holmes, Sam Bankman-Fried, Kenneth Lay and Jeffrey Skilling all went to prison. The acclaimed genius behind the poster child of a company whose employees found meaning in doing business differently, Zappos, turned out to have been doing ketamine and whippets fifty times a day and was convinced he was morphing into a crystal when he finally died in a storage room dumpster fire. Adam Neumann’s mission to ‘elevate the world’s consciousness’ turned out to be a euphemism for elevating his own bank account while leaving shareholders holding the bag. When the titans of technology met President-elect Trump at the Tower of Mordor in December 2016, they knelt at the foot of evil and gladly kissed its ring.

From a broader perspective, we are boiling the planet underneath our feet, yet keep adding fuel to the fire daily. The founding myth of capitalism, that infinite growth is possible in a finite physical system, has always been risible. Humans and domesticated animals account for 97% of global mammalian biomass. At this point, it is inevitable that we will cross the 2.5C threshold within two generations and precipitate a global extinction event. This will doom the few ragged remnants of humanity to a future of consuming insect protein bars while sheltering in caves from the blistering, unbearable heat while ocean waves lap at the windows of office buildings in New York, Rotterdam and Hong Kong. Yet globally we continue to subsidize the fossil fuel industry to the tune of $2 trillion annually. Exxon Mobile was hiding prescient studies about global warming back in the 1970s; the US government has sabotaged the work of global climatology for generations. The problem and its solutions have been known for decades13, but our global polity continues to behave like a cirrhotic drunk with a liver the size and consistency of a basketball who nevertheless hides fifths of vodka under the sink. As Friedrich Hayek commented presciently in the Road to Serfdom, “We are ready to accept almost any explanation of the present crisis of our civilization except one: that the present state of the world may be the result of genuine error on our own part and that the pursuit of some of our most cherished ideals has produced results utterly different from those we expected.”

No matter what you do, for what company in whatever field, you are one of a billion workers shoveling coal into the furnace of a train bound toward oblivion. You are one of trillion metastasizing cancer cells in the guts of our planet blindly consuming their host as efficiently and quickly as possible. Irrespective of what you tell yourself, you are part of the problem, not the solution. There is no solution out there to be part of.

Do not try and kid yourself that whatever company you work for is doing something unique or irreplaceable. Nokia had a functioning prototype very similar to the iPhone years before Apple released it; it would have appeared sooner or later, with or without Steve Jobs. The airplane would have been invented without any Wright Brothers, as would the Model T in absence of a Henry Ford. Penicillin would have been discovered even if Alexander Fleming had been hit by a bus in his childhood. Someone would have invented the modern travel suitcase even if Robert Plath had not had his flash of inspiration in 1987. The Butterfly Effect would have been conceptualized even if Edward Lorenz had been able to wait another hour for his coffee break. Companies and people never truly invent anything; they merely find themselves at a moment of technological serendipity and are smart and fast enough to act on it. Make no mistake, the world will get wherever it is going with or without you.

The conclusion I draw from this, and that you must draw from this, is that it doesn’t matter a dingo’s kidney what you do, or for whom. No job, role, title, company, or field of work has any intrinsic meaning. It’s no better to be a doctor than an arms dealer. You might as well sell diapers, insulin, tobacco, Prozac, warships, cluster bombs, or vacuum cleaners. Nothing matters. Neither you nor your company will change the course of history, which hurtles inexorably toward catastrophe and ruin; or even your industry, which will endure the same vagaries of boom and bust to which it was always destined. You may as well enjoy the ride as long as you can, and ensure that those you care about have the same opportunity.

The only point of work, it follows, is financial independence, not subsistence. Let me emphasize this. Why do we work? We work so that we don’t have to work. This is not an answer. It is the answer. It is the only answer. Anyone who tells you different is lying, and most likely with the aim of getting you to work for them so they won’t have to work themselves. Achieve financial independence as soon as practically possible. Decouple yourself and your fate from this monstrous machinery of employment. Free yourself to enjoy life while we still can. Join a theater troupe. Write a book. Sponsor your local baseball team; why not become a coach? Take up ultramarathoning. Spend a week touring Berlin sex clubs. Make your own hotsauces, smoke your own ham, pickle your own pickles. Become a mycologist. Take a course in watercolor landscape painting. Embarrass yourself during open mic night at your local pub. Retire to the Yucatan, or Costa Rica, or Lombok. Do anything except trudge to an office every day to perform pointless tasks for the benefit of hideous people in the furtherance of ghastly, unsustainable ends.

No job or company or accomplishment is meaningful except insofar as it helps you achieve this goal; no job or field is intrinsically bad or evil unless it prevents or hinders you from achieving them. Maintain clarity about your true mission and do not allow yourself to be distracted from it. Ideally you want to be in a position of financial independence as early as possible and to make the most money with the least amount of work and stress, leaving time for personal projects and investments and accumulated capital for your children.

Graveyards are full of people who died poor after a lifetime of work they found meaningful or important which then rapidly evaporated into insignificance, leaving their families nothing but debt and misguided lessons about the importance of hard work. This serves no purpose except to continue the cycle of pointless servitude. But this cycle of serfdom can be broken. This book is about how to break it.

2. Corporations are people too (just not ones you’d want to spend any time with)

“Now listen, you rich people, weep and wail because of the misery that is coming on you. Your wealth has rotted, and moths have eaten your clothes. Your gold and silver are corroded. Their corrosion will testify against you and eat your flesh like fire. You have hoarded wealth in the last days. Look! The wages you failed to pay the workers who mowed your fields are crying out against you. The cries of the harvesters have reached the ears of the Lord Almighty. You have lived on earth in luxury and self-indulgence. You have fattened yourselves in the day of slaughter.”

- James 5: 1 - 5

Much has been made of the Citizens United Supreme Court decision in the United States in terms of corporate personhood and the concept of granting legal entities the rights of persons. The concept is much older than that. Even the word ‘corporation’ derives from the Latin corpus, or body. Case law clearly accepted the notion of a company as a ‘person’ in the United States from the early nineteenth century, and far earlier in Great Britain.

Joel Bakan’s well-regarded work The Corporation on the topic established the contours of this argument succinctly. The modern corporation, conceived as a person, is devoid of all moral constraints, having relieved its shareholders of any liability for its actions and free to attract those willing to stomach whatever behavior then results. It is extraordinarily powerful, able to marshal vast resources under the all-seeing, unblinking eye of executive oversight. It is immortal, unless it manages to destroy itself or is in turn consumed by a more efficient predator. Finally, as I pointed out earlier, it is legally bound to seek maximum shareholder returns to the exclusion of all else. This latter aspect fulfills the clinical definition of psychopathy. From the spectacular ecological carnage of BP and ExxonMobile to the legions of Oxycontin addicts to Nestle’s gruesome cocoa plantations in Africa, and Amazon delivery drivers with their urine filled bottles in the passenger seats of their cars, it is absolutely clear that the only real crime from these companies’ point of view is getting caught. Employee health, safety and well-being, human rights, the environment, national security … these are all simply costs to be externalized. Compliance is a matter of cost-benefit analysis, nothing more. I cannot count the number of times I have presented a regulatory or legislative mandate to management, only to be immediately asked about the relative cost of compliance versus penalties for ignoring it.

Once when I was a student, I had a summer job for a couple of years erecting tents for weddings and other events. We had periodic health and safety trainings, which we immortal, invulnerable teenagers obviously found desperately tiresome and cause for much mirth. One time the guy who’d been delivering the training about some obscure OHSA rules stopped in the middle of his talk, glaring at the yawning, laughing hooligans he was trying to help. “You stupid little shithead fucks,” he growled at us. Something about his demeanor shut us up quick. A deathly quiet descended. He continued. “Do you know that every goddamn rule in this handbook, every labor law on the books everywhere in the world, is written in blood? The blood of people like you and me. They died so you could work in safety. Your employer could give a fuck if you live or die, or lose an arm or an eye. There are always more dumbfucks out there ready to take your place. These rules are made for you, not for them. Get it straight, assholes.” I have always remembered that moment, when the pure, raw, inescapable truth of that statement struck me like a baseball bat in my gut.

My intention here is not to re-litigate this argument of the corporation as soulless psychopath, which at this point has been established so definitively, the behavior of the largest offenders so cartoonishly malevolent, it hardly bears repeating. What I do want to do is explain what this means for you in your everyday circumstances, and your long-term plans.

In terms of your immediate situation, working for a company is the equivalent of being locked in a room with a heavily armed psychopath. Behave accordingly. So long as you are useful to the firm, it will behave itself, even shower you with rewards and praise. This may change, drastically, without a moment’s notice.

In my first executive VP role, we had a saying which has half a joke, half not. “Feed the bear, or the bear will eat you.” We made sure we fed the bear and kept it satiated as far as we were concerned. But the bear is never satisfied. If someone else fails to feed it, it will eat whatever is at hand. The shareholder always comes first, and the shareholder wants EBITDA growth. That means either revenues go up, or costs go down. The preference is always to increase revenues – costs can be reduced later. When revenue dries up, they come for costs. And you are a cost. I went through many rounds of cost-cutting during the financial crisis of 2008, and I had to let go many people I would have preferred to keep, and whom I believed the company should keep as they delivered significant value or had real potential. But in the end, you cut the people you can afford to lose in the current budget cycle, not the ones you’d prefer. It’s similar with assets in a cash crunch. You sell what you can, not what you want.

I am not saying this to justify actions I feel badly about, but to explain to you what will be in the minds of your superiors when a crisis arrives. Do not make the mistake of thinking that because you are loyal, valuable, accomplished, or talented that you are not necessarily expendable. These words are not antonyms.

Companies will tell you that you are important, vital even to their success. That the human element is what makes them unique. They depend on you, and for that reason they care about you, your welfare, your development. They want the best people, which is by definition, you. They will invest in you, so that you become a more productive and well-rounded employee, and more value generating to the firm at the same time.

Lies. The intention of all this meaningless chatter is to increase your productivity without a corresponding increase in your compensation; to retain the most productive; to create a feeling of responsibility, of indebtedness. The entire system is designed to reduce your expectations for compensation and advancement, substituted by the notion that you are building some kind of fictional equity which will be converted into economic value at some point in the future. Do not imagine that because what you do is important or even vital to the company that you are safe. There will always be some pig-headed manager above you eager to dispose of you precisely for this reason, consequences be damned.

Now, I’m not saying you are not building this equity. Learn what you can in every job you have. Gain whatever skills are accessible to you. But do not expect that this will be rewarded by your current employer. Also keep in mind that most people drastically overestimate their own difficulty to replace; you are probably among them.

There are five vitally important trends you need to understand when planning your long-term future and path toward financial independence. First is that while there has been an enormous increase in productivity over the past decades, nearly all of this surplus accrued to the owners of capital, not labor. Second, the tax contribution of major companies has been in long term decline: these astonishing profits no longer fund public services. Third is the massive concentration of compensation in upper management at the expense of the average employee. Fourth is the ever-greater concentration of wealth and assets. There is an ongoing game of musical chairs in the global economy where there are fewer and fewer seats at the table of sharing in the gains of economic productivity. If you want to claim one of those chairs, you must ascend in management and you must begin to accumulate assets quickly before the bear finally turns on you, as it will. Fifth is that the traditional social safety net you might otherwise rely upon on to save you is fraying rapidly. Do not count on it to save you from a lifetime of unwise profligacy.

Labor’s share of national income has been in steep decline for decades. This became particularly pronounced after 2000. While it is not uniform, it is happening everywhere, and it will continue. There have been certain moments in time, generally after crises – the Black Death, World War II – when a shortage of workers has meant that labor is sufficiently scarce to increase its share of profits and the productivity surplus. Largely, over the course of economic history, this has not been the case and labor’s share of economy-wide profits has been under constant downward pressure at the expense of capital.

One of the most important drivers of this is where and how income growth has been created. Globally, there has been an incredible growth in profitability of technology firms. These firms employ relatively few people and instead rely on intellectual property, massive R&D and capital expenditures and intangibles. The top 10% of large firms capture 80% of economic profit2. Google and Meta together for instance employ about 270,000 people globally whereas the two largest telecom companies (China Mobile and Deutsche Telekom) employ 700,000. The four largest technology firms have a market capitalization of $8 trillion dollars, or $4 million per employee versus for example $500,000 at Deutsche Telekom.

As corporations have accumulated wealth, they have also drastically reduced their contribution to society. Between 2000 and 2021 the share of corporate tax as % of GDP in the United States fell by half. As corporate profits have sailed ever higher, corporate taxes have continuously fallen.

One of the modern corporation’s favorite parlor tricks is to pretend they have substituted tax payments with their own social investment programs – formerly known as CSR, now commonly seen under the rubric of ESG. I have spent enough time in boardrooms when the topic of ESG comes up as people roll their eyes and begin scrolling through their phones to assess how much importance senior executives attach to these initiatives (less than zero). The more clever ones are able to put up a more sustained charade of interest, but even then make no bones about ensuring these investments go back to financing their core business at the end. When you boil things down, the lion’s share of ESG involves capturing government subsidies to do things they would have done in any event – constructing solar panels on the rooftops of warehouses, building mobile phone masts or fiber optic networks in rural Africa, and so forth. What investment is made in less advantaged communities, the environment, bridging the digital divide or whatever the cause du jour is, corporations will frequently spend a 3 – 4x multiple of the investment on communication of that investment to the public so everyone knows what ‘good citizens’ they are.

To summarize: ESG is a gigantic global self-congratulatory PR circle jerk designed to suck subsidies out of governments and paper over the ever-falling tax contributions to budgets.

As tax take from corporations has fallen, debt has risen. In ten years in the United States, interest payments on debt more than tripled to nearly $700b, or about as much as the budgets for their global war machine of oppression and occupation. Given that the top 1% of households own over 50% of equities and bonds, and the top 10% hold over 90%, this is obviously a gigantic transfer of wealth of about 3% of GDP from poor to rich happening every year, and at an ever-increasing rate.

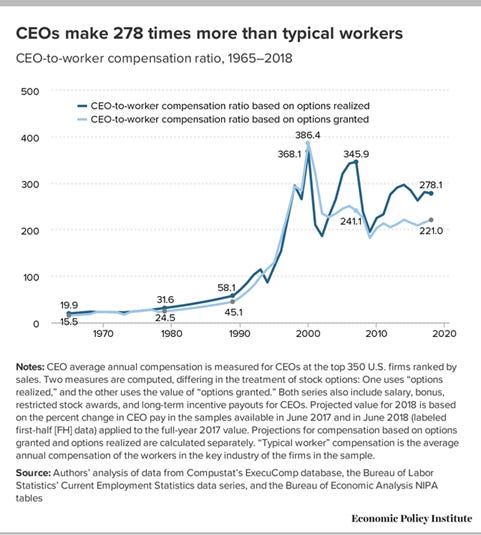

This is of course in addition to the ever-growing gulf of compensation between the highest paid managers and the lowly employees and gig workers who fill out the ranks of the modern corporation. While 50 years ago a CEO would typically be compensated at 20 – 30x that of the average worker, this has now exploded to 200 or 300x.

If you work in a corporation, rising to the intermediate and senior level of management places you on a logarithmic, not linear, upward scale of compensation.

The emerging consultant class bears a great deal of responsibility for this trend. It has been widely remarked upon that McKinsey’s executive compensation practice has at times constituted half of the firm’s billings. In The Firm, Duff McDonald comments on the other side of the equation that McKinsey has been the “impetus for more layoffs than any other entity in corporate history”. Not to pick on them particularly, of course. Bain and BCG are no better, only less successful at what they do. The consulting industry is devoted to the creation of enterprise value, to the exclusion of all other considerations. In the past this may have concerned ending defined benefit pensions, offshoring of manufacturing, and reduction of health care costs; today, it is centered on investing in technology in order to reduce long term operating (eg human) costs.

The generative AI revolution will only accelerate this trend. While generative AI has recently made a media splash, this technology has been slowly chipping away at labor intensiveness of processes for many years. Even back in 2017, a Japanese insurer, Fukoko Mutual Life, fired its entire actuarial department and replaced it with an AI agent. Goldman Sachs estimates the technology will eliminate up to 300m jobs globally within a decade. The last tool labor has remaining with which to demand a fair share of the productivity surplus is the fact that it is needed. Once AI renders much of our effort moot, even this will begin to dissipate.

The AI revolution will either usher in an era of equality and abundance, or an ever-accelerating concentration of wealth which will mean one of the few jobs available is volunteering to be hunted from helicopters by scions of the oligarch class. If we take the past as prelude as to what the future holds in store, you would be wise to bet on the second scenario. What this practically means is that you must accumulate as much capital as you can so that you don’t end up on the wrong side of the line.

If today you are a well-paid individual contributing professional or a low-level manager, beware. These trends are coming for you, quickly, and at an ever-accelerating rate. Imagine yourself as a harp seal on a small piece of ice while orcas circle lazily in the black waters below. This is the situation of a professional in the modern economy. You need to get to safer terrain as quickly as you can. And by ‘safe’, I mean financially independent.

All of the aforementioned trends are intended to, and have had the primary effect of, increasing the concentration of global wealth in the hands of a few and widening and deepening the moat around themselves to prevent others from joining. According to the latest UBS Global Wealth Report, the top 1% of wealthiest families globally own 45% of the world’s wealth.

Share of top 10% of households on total wealth 3

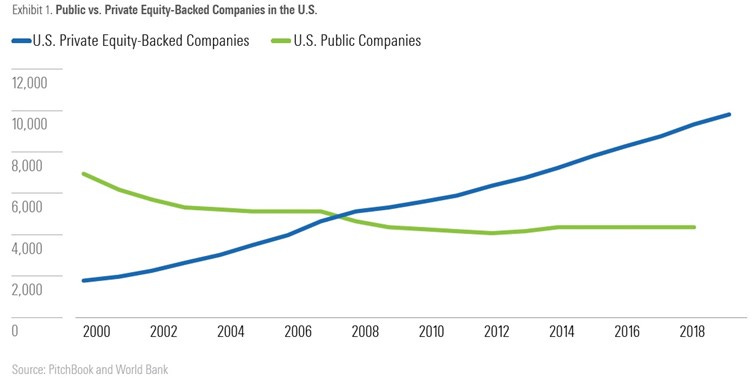

As the wealthy get wealthier, they also ensure that they hoard the best investment opportunities for themselves, like giant swine driving away rivals from an overflowing trough of food. A little-remarked on fact is how many companies have exited public stock markets in recent years. In 2000 there were 5,500 listed companies on exchanges in the United States; in 2020 this had fallen to 4,000. During that period 3,300 companies were taken private by funds or their owners/ managers4. Investment in these enterprises is now available only to the elite cadre of the global rich served by wealth managers and with access to the top PE and hedge funds. And of course, these people are not fools. They bring these companies private because they see outsized returns available from doing so, leaving the chaff for the plebian hordes investing on Robinhood.

Many people assume that the state pension program will fill in some of the gap left by their failure to invest. Do not rely on this. I don’t want to get into a lengthy digression on this topic, as it is vast and complex and I am not trying here to make political arguments one way or another. Nevertheless, take a moment to consider this practically. Look at the average pensioner living primarily on social security, public pensions or whatever it’s called in your part of the world. Is this a lifestyle you would enjoy? Most likely not.

Now consider that in virtually all cases, this is the best it is going to get. Public pensions the world over are set to collapse due to the inevitable mathematics of demographic change. Universally in the G-20 where most of you live, fertility rates have been below replacement levels for decades while lifespans of the elderly increase constantly. In the EU, the last time any country had fertility rates above replacement level was Ireland in 1995. Populations will decline, the elderly will cling to life for decades past retirement, with the result that the dependency ratio of elderly to working age people will increase asymptotically. The only stable solution to this problem is massive and sustained immigration, but this is politically unpalatable in most places. Therefore the value of any public pensions available will decline precipitously over coming decades in most countries. In 947 out of 1169 regions in Europe, the old age dependency ratio will be over 50% by 205029. This means every working person will need to support half of a pensioner wandering around in a park somewhere with his or her weiner dogs. Keep this in mind when thinking about your future. The Boomers are all preparing to set sail across the River Styx leaving economical and ecological carnage in their wake, singing as they go, “après nous, le déluge!” Do what you have to do to make sure you are not swept away in the current.

Let me recapitulate:

· Corporations behave like remorseless psychopaths because they are. They are driven by the profit motive and nothing else. As Utah Phillips once observed, “the profit system follows the path of least resistance, and following the path of least resistance is what makes a river crooked.”

· These companies are owned and run by the top 1% and exist to generate profit for them and create an ever-increasing gulf between themselves and labor. A terrifying arsenal of public lobbyists, management consultants and technological advancement ensures that surging economic profit goes to them and stays out of the grubby hands of proletarians. Both income and wealth are far more concentrated than they ever were, and this trend will continue indefinitely. Profits are always privatized, risks are socialized as much as possible.

· None of this is likely or frankly even possible to change as the tools of the 1% to control and manipulate the masses - and hence public policy - get more powerful and sophisticated, and a willing army of paid mercenary managers and consultants take on the role of enforcers (note: you are here). Do you remember when the Panama Papers and subsequent Pandora Papers were released containing terabytes of painful detail about how the wealthiest business people, celebrities and politicians on the planet hide their wealth to avoid scrutiny and evade taxes, and absolutely nothing happened except that one poor Maltese journalist was incinerated in a car bomb for her effrontery? Well, Pepperidge Farm remembers, even if no one else does. This is the reason why nothing can or will change.

· It will therefore become ever harder to break out of the role of enforcer and become an owner. You need to take action, now, if you ever wish to do so.

· The state will not save you. The currently retiring generation is the last that has any surety of enjoying the fruits of its labor via an adequately funded pension scheme. You will receive the scraps that remain, if anything at all.

By the way, if you are wondering what the really smart money is up to, there is a very quiet but burgeoning subset of consultancy services advising billionaires how to future-proof their apocalyptic boltholes. There’s no point in having a self-sufficient, fortified compound with a private airstrip and submarine pen somewhere in rural New Zealand if your mercenary fighters simply decide to shoot you once civil order collapses so they can enjoy the fruits of your planning themselves. So the next time you’re worrying about the next mortgage payment, spare a thought for the poor decibillionaires trying to figure out how to make an app on their phone that will allow them to detonate explosive collars on their palace guards should they begin to sense hints of unrest. There are reports that The Zuck’s billion dollar fortress in Hawaii has a moat that can be set on fire to incinerate intruders. I know this all sounds like a bad joke, and I wish it were. It’s not.

3. Loyalty is a no-way street

“I need loyalty. I expect loyalty.”

- Donald Trump, to James Comey

The first thing you learn making corporate presentations is to start at the end. Tell them what you’re going to tell them, then tell them.

So let’s start at the end. It’s closer than you think, so you’d better get ready for it. This company you have been loyal to and served devotedly will dispose of you the moment it finds a more cost-effective alternative, be it digital or another animate blood bag like yourself but in a cheaper geography, so prepare as best you can. They will demand commitment but they themselves will show all the loyalty of a house cat chewing the face off its dead master once it experiences the first pangs of hunger.

Years ago, a friend of mine who worked for a medical instruments manufacturer told me an interesting anecdote. He had hired back someone to their company who had left a few years previously. They had been through a long discussion about what he had learned in the interim and how this would add value to the company. My friend’s boss got wind of this and demanded he release the re-hire immediately.

This stout fellow, to his credit, would not budge. “I will not,” he said in his charming northern English, Manchesterian brogue. The re-hire had given notice at his job with the assurance of his return to the old company; my friend could not go back on his word, in this situation. After much back and forth, the higher boss acceded. “Loyalty counts,” he growled, ending the meeting.

But loyalty does not count. Or rather, it only counts one way. At my first EVP role, we were having a function to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the company’s founding. Important context: in between it had been bought by a multinational conglomerate for a vast amount of money. As I was running the festivities, I suggested to the CEO that maybe we should honor the people who had been there since the beginning and made it what it was. Of whom the CEO was one, it should be noted. She was the company’s third employee in its entire history.

She sniffily dismissed this notion. “We have too many people who have been here too long. I don’t want to encourage this kind of thing.” Clearly she had been in some meeting with global management and been told something to the effect that the company was stuck in its old ways and needed fresh blood. Now, this attitude was simply odious. She herself met this criterion, and she had made an astonishing amount of money from the buyout and subsequent CEO tenure. She was already financially independent many times over. Yet she was unwilling to make even a symbolic nod toward those whose hard work and sacrifice had gotten her there over the previous decade because of offhand commentary from some functionary at global HQ, who in any event had obviously been thinking of much older and more established branches of the business than ours. Nevertheless, keep in mind this was one of the largest and most well-respected companies on the planet, and its message to local CEOs was more or less “fuck loyalty”. I suspect they are not alone.

What I also want to point out is if even this one individual who had gained so much from her people’s loyalty could not bring herself to lift a finger to acknowledge them, what can we expect of a faceless corporation? If you guess nothing, you would be correct. Get yourself a cookie.

Just before her ticket finally came up, she went through a spasm of throwing an executive out of the company every three months in a last effort to save her own skin. Like a desperate sea captain throwing sailors to sharks trailing her lifeboat, she cast people out one after another. But blood in the water only attracts more sharks. I was unfortunately the last one out before she got the boot herself. In spite of everything she sacrificed in terms of loyalty and decency, she was still discarded like a piece of random junk when the time came.

Statistically in fact, her path was not abnormal. The average global tenure for a CEO of a large company is about five years5. Executive officer tenure at CEO-1 is less than this. It is ridiculous to expect long-term thinking or consideration of loyalty from people who know from the outset they are likely to be gone in four to five years not matter what happens and will be booted in two if they do not demonstrate convincing and tangible results.

I chose the citation at the beginning of this chapter precisely because of its absurdity, Donald Trump is infamous for demanding total loyalty while demonstrating none himself. He is a buffoon, but a successful buffoon, all things considered. He is the extreme outlier that nevertheless confirms the norm. While most individuals or companies would not be so brazen in their hypocrisy, as usual his only real crime is saying the quiet part out loud. The moral and behavioral distinction between the Trump Organization and any other Fortune 500 corporation is one of degree, not principle.

My advice is to prepare yourself for exit from day one. Firstly, prepare yourself psychologically. As I wrote earlier, remember that nothing you are doing actually matters. Sure, take some pride in your work and do a good job, but do not wrap up your identity in service to a bunch of bozos who would grind you up and sell the remains as animal feed if they could get away with it. Keep an appropriate psychological distance. Your job is not your identity, your boss is not your friend, your colleagues are not your family. If you got hit by a truck tomorrow, they would replace you in a week and have forgotten you completely in a month. Maintain the same attitude toward them.

Second and very importantly, collect everything. Bring everything you can home from work and keep a filing system. Take meticulous notes, and particular note of any health and safety violations, legal or regulatory infractions, corporate malfeasance, tax avoidance, or violations of labor law. Invest in a discrete recording device for key meetings. Ferret out bad behavior by the executives; there are surely numerous financial, sexual and/ or substance-based indiscretions occurring, you simply need to find them27. Find out what corporate IT logs and does not log in terms of behavior (will they know if you backup your hard drive regularly to an external device or cloud account, for example). Take notes of conversations with your superiors as contemporaneously as possible, with secret recordings if these are not electronically defended against or illegal in your jurisdiction. Keep particularly good records of anything to do with your personal goals, performance, evaluations and any irregularities therein.

While I am not suggesting to extort or blackmail your colleagues or your company, it is certainly better to be in possession of and in command of all relevant facts when the inevitable clash comes. Their attempt to exit you will be a key moment where a great deal of compensation is at stake, not to mention your reputation.

A few months before my CEO decided to cancel my position, I was warned this was coming by various sources in the company. Knowing her pettiness, it was clear to me she would try to strip me of my bonus as part of the exit, to demonstrate her ‘toughness’ to global HQ as well as provide a justification internally for disposing of a well-liked and effective executive.

Sure enough, a few days before the close of the fiscal year, her EA began to instruct me to add certain goals and targets to my KPIs which obviously could not be met at that point. Some she told me to add less than twenty-four hours before I was dismissed. When the HRD smugly told me how small my exit package would be due to non-performance, I was able to present her with an already prepared, extremely detailed letter addressed from my private lawyer to the global compensation committee members outlining how the company had dropped in unachievable goals at the last minute in order to avoid paying out a well-deserved bonus, with an annex full of time stamped e-mails. She turned white and immediately agreed to my terms.

In my back pocket, I also had information about how some members of the HRD’s team had been caught buying property on which company assets were built through shell corporations, then agreeing to pay themselves exorbitant rents. A Big 4 forensic audit has been launched which she and the CEO conspired to quash – fortunately I got what I wanted without having to deploy such a ‘nuclear’ option, which would have had unpredictable consequences.

Be prepared, and never bring a knife to a gunfight. And always assume it will be a gunfight. If possible, bring a bazooka, but don’t use it unless you have to. They make a lot of noise.

These points have related to the end game in the company, which will not come often but must be well-prepared for as it will come, no matter how good you are or how well you perform. The further you rise in management, the more political the position. At this level there is often an ever growing disconnect between performance and tenure. This accelerating insecurity is part of the reason executives are compensated so handsomely.

A less urgent but equally important point is to remain rational in the company of well-intentioned but ultimately powerless managers striving to convince you to sacrifice something in the name of the company. While this sounds easy to dismiss – of course I will look out for my own interests instead of those of this soulless corporation – this becomes exponentially more difficult when your manager presents it as a personal favor, or that your leaving is a personal betrayal, or how much of your work your colleagues will need to take on, or how much they have invested in you, or whatever sad story they concoct.

These people didn’t get into their roles by being bad at what they do. You must remember that all corporate relationships are transactional. They are trying to get you to act on personal empathy to make an irrational decision that benefits the company because it also benefits them as a manager. Remain disciplined, stick to your plan, ignore their pleas to personal loyalty. Any loyalty you show them is wasted. They will drop you like a hot coal as soon as they have a better opportunity elsewhere.

Once I left a pretty well-paid and satisfying job in a company for something much more interesting in another division of the same company. My manager sat me down for an hour and tried to talk me out of it, employing every trick in the book. I was twenty-eight and I quite liked him. He was a tall, insouciant Scandinavian fellow with a keen intelligence and quixotic sense of humor. I admit that I nearly cracked under the pressure. But I held fast, stuck to my original plan, and took the new job. This was instrumental to my further development, and I never would have gotten where I did without it.

A few weeks later the Nord had also left his job for something better. All his chatter about loyalty and commitment and obligation was so much dust in the wind. He had certainly been far down the path of negotiations for this new role when we spoke. Did he care? No. Should he have cared? No. Should you care about whatever twaddle your manager is spouting at you about your next move? No, no, no. Loyalty doesn’t count. It never has, and it never will. Anyone who says differently is probably trying to get you to do something you shouldn’t.

4. Spit, don’t swallow: regurgitate the corporate Kool-Aid as needed, but never drink it

“And those who were seen dancing were thought mad by those who could not hear the music.”

- Friedrich Nietzsche

As you ascend the corporate ladder, you gain both direct and indirect influence; you will also attract more and more attention. Your words will be repeated as a source of authority, for good or ill. They will also be carefully parsed for adherence to corporate goals and objectives. While these goals will frequently appear meaningless or even destructive to the company and its ability to create value for shareholders, it is vitally important not to appear to block them or to have a negative attitude.

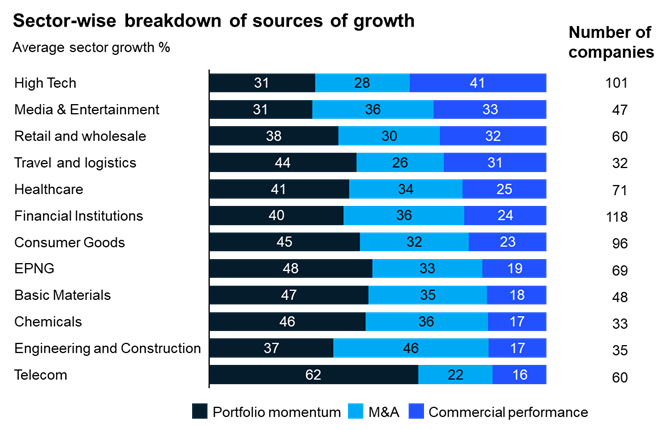

This requires a bit of nuance and elaboration. Every firm on the planet desperately chases after increased shareholder value. This comes from three main sources:

· Momentum and inertia of the business

· Structural changes in the market/ M&A

· Commercial performance

The weight of these depends quite a bit on the industry. For instance, in telecommunications, simple momentum is responsible for most variance in profitability and shareholder value. Bigger companies tend to succeed and defend predatory pricing, smaller ones tend to struggle. When the market is growing, everyone grows, and vice versa. I spoke to the regional CEO of a global telecommunications concern once who remarked, “One of my biggest problems is that a monkey could have successfully run a telecoms company in the 90s and 2000s. Now our whole industry is full of people convinced they’re geniuses and the sun shines out of their assholes just because they got up and came to work on time during the right decade.” Utilities are governed by regulation, high tech firms are dependent on successful execution of hundreds or thousands of M&A projects, whereas firms with low barrier to entry such as consumer packaged goods or internet retail tend to see the most reflection of commercial performance in shareholder returns.

Source: Growth Decomposition Database, McKinsey & Co. 2014

Nevertheless, in most industries commercial performance accounts for a minimum of results variance, yet corporations are still expected to come up with sophisticated plans and initiatives. Every new executive will have his or her signature initiative or strategy whose benefits you will be expected to trumpet at every opportunity; moreover, everyone will be expected to deliver evidence how these initiatives are delivering immediate and sustainable value.

It is important to distinguish between what you have to deliver and what you are expected to parrot. You will have your day to day line responsibility, whatever that happens to be. This will have a series of goals set which help keep the company running smoothly. You must deliver this, which will be a key part of your evaluation and advancement.

Most companies also have a second factor in evaluation which is not what was delivered but how it was delivered. This is often given a veneer or objectivity but in fact it tends to degenerate to compliance with the corporate agenda of gibbering jargon. Do not dismiss the importance of this merely because of its irrelevance to practical results. It will be your undoing.

I once worked for a company which had a history as a quirky upstart but had been bought by a big multinational corporation. Most of the people in the executive minus one level had been there for many years and had solid records of accomplishment behind them. When the central HQ sent in their pompous foreign executives to manage their new property, these established professionals found great mirth in playing “Bullshit Bingo” where various terms of meaningless corporate jargon were marked off on cards. Their surreptitious activity turned out not to be as surreptitious as they thought, and most were gone in a year or two. There are armies of people in any corporation devoted to enforcing adherence to whatever flavor of industrial groupthink happens to be in fashion at the moment. If you want to make money off of these people, you need to play their games, by their rules. Be the good soldier in Red Square, nearly dislocating his shoulder as he salutes the Czar. Did the Roman legions laugh at Caligula when he declared war on Poseidon and ordered them to fight the very ocean itself? They did not. They plunged their spears into the waves as though their lives depended on it. As they did. As does yours.

I don’t mean to imply that what your corporate masters routinely demand of you is as demeaning and ridiculous as Caligula’s war on the sea. I mean to say it straight up and directly, as clearly as I am able, without the slightest hint or trace of ambiguity. Reconciling yourself to this carnival of the absurd is a burden, but one you must learn to bear with a smile and good humor. Like Nietzsche’s inaudible music, the performative dances corporations require you to do seem senseless and absurd to the casual observer, but this makes them no less vital to your future well-being. The very absurdity of these rituals is what imbues them with meaning from the corporation’s point of view. In Japan, employees historically had to gather together and sing odes to their company every morning. People can hardly be expected to show or feel extraordinary devotion by acting and behaving like normal people. Deviation from the mean is the goal, not a consequence.

In that same company we had a CFO from abroad who was really very good at her job. She was so good the CEO hated her and attempted to undermine her at every opportunity. But the CFO had an ace in the hole: she lashed herself unapologetically to promoting the propaganda coming from the center; i.e. her bosses’ boss’s agenda. An attack on her came to be seen as an attack on the Group CEO. Within a year the local CEO was gone and the CFO herself went on to a stellar career in the Group corporate functions, and much larger and more important national operating companies than ours. Now this woman was absolutely brilliant, and I am certain she found these ritualized incantations of corporate doublespeak as tiresome and humiliating as I did. But you’d never know that from talking to her, even in private. I have always admired the tenacity and discipline she demonstrated in that regard, though it was a skill I was never able to learn myself. I wish I had.

She recently took a job working for one of the company’s great rivals in a very sensitive position. The stakes in this particular market in this industry are at the moment absolutely existential. I won’t bore you with the details, but it’s a very difficult moment for a very important market. After a couple of decades of professing allegiance and parroting endless tropes about loyalty to the company, when the right opportunity came she pounced instantly with clear-eyed rationality and no hint of doubt or remorse, straight to a position where I expect she will wreak absolute havoc on her former colleagues. And good for her, I say.

5. Turning Income into Wealth

“I don’t like money, actually, but it quiets my nerves.”

- Joe Louis

Achieving financial independence or at least acquiring a sufficient financial cushion that you do not feel pressured to accept roles you do not want, can survive a reasonable period between jobs without wages, and enjoy a flow of passive income all come down in essence to your ability and willingness to turn your income into wealth. And by wealth, I specifically mean productively invested financial assets. This seems like an elementary and painfully banal point, but many people – even those with very high incomes - do not manage to do this early enough or to a sufficient extent. To take an extreme example, 78% of professional football players experience “severe financial hardship” after retirement21. This includes those who made tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. It can also happen to you if you are not careful.

I am not going to spend time on basics here. I assume if you are reading this book, you know that you need an emergency reserve fund; that you should get rid of credit card debt at 19% APR as quickly as possible, whereas there’s not much point in paying down a mortgage with a fixed rate of 2.8% if you can safely invest the same capital at 8% somewhere else and this sort of thing. It’s just math. My intention here is rather to discuss how to avoid some common mistakes people make at the next level of sophistication, which is when and how to deploy capital productively.

Much has been made of studies where people with very high household income actually live more or less paycheck to paycheck. Over half of American families with household income of at least $100,000 per year say this is the case18. High incomes serve no real purpose if everything is eaten up by lifestyle creep and you find yourself working to maintain that lifestyle into your 60s. Additionally many people fall into the trap of assuming that once they have reached a certain income level, they are more or less guaranteed to stay at that level or higher for the rest of their career. This is not true, and it is a dangerous misconception.

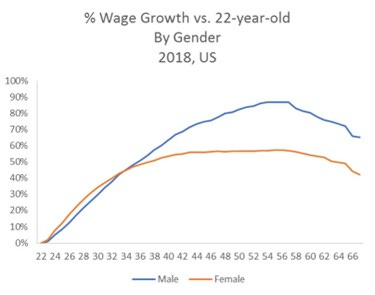

Income tends to peak in your early forties as a woman and fifties as a man15. Keep in mind this median degradation disguises a great deal of variance. For every Boomer lawyer or tenured history professor still hobbling into the office at the age of 74 for $250,000/ year and asking his or her Millennial assistants to help create PDFs or change the printer cartridges, there are another three who got canned in a “reorg” where redundancies were suspiciously concentrated in the 55+ age bracket and are now greeters at Walmart or holding stop signs on construction sites and breathing diesel fumes all day long.

Once you cross this threshold you are in increasingly dangerous territory. Health problems are more likely to arise; a stroke or cancer diagnosis may drastically change your situation in a moment, both in terms of costs and ability to generate income. If you lose your job at this point for whatever reason, in many fields ageism will become a factor. You do not want to find yourself desperately searching for a high-income job at age 53 which simply may never materialize. You need to begin turning income into wealth at an early age and be sure you can ensure at least a reasonable subsistence through investment income by age 45 or 50 at the latest. Generally, I advise people to work off the assumption they will not have regular corporate work after the age of 50.

Source: Payscale

Robert Kiyosaki’s celebrated if simplistic Rich Dad, Poor Dad makes one vitally important point, which is that many people confuse assets with wealth. While from an accounting point of view a big house, a garage full of nice cars, drawers full of jewels and expensive watches, and a vacation home are indeed assets, they do not generate income. They often depreciate in value and will only add to your cost base through property taxes, insurance, registration, upkeep, etc. Kiyosaki takes the view that anything which does not produce a positive net income stream is in fact a liability, and there is a great deal of truth to this sentiment.

Many people are attracted by the idea of founding a startup, inspired by the stories of those who have achieved great wealth and renown by doing so, and see this as a path toward independence. My advice is not to go down this path until you are already independently wealthy and can afford to comfortably lose your entire investment. Statistics are not on your side in the startup game. 21% of US startup businesses fail within 12 months and half within five years19. Startups require enormous amounts of energy and time; time when you should be at the peak of your earning power. If you fail, you will have expended some of your only irreplaceable asset – time – in addition to the capital and energy you have devoted to this. Equally importantly, you may compromise your reputation for effectiveness and capability.

People say they respect those who try and fail, but this is often not true. It is very common to publicly applaud those who risk and fail while quietly mocking them in private. While you may get new contacts and skills, opening new pathways to success, you will also close off many others. Do not be so enamored by all the success stories you see heralded in the press that you forget about the uncountable numbers of those who failed and deeply regret having tried. No one writes about them in magazines, but it is an inescapable reality. Additionally, those of you outside the United States may find the reality of closing a company and bankruptcy a far more punishing experience than in New York or San Francisco, and with more lasting consequences; there is a reason why so many start-ups and unicorns originate in the US that is wholly separate from the concentration of talent and capital.